Lexx, “The Game”

Season 4, Episode 18

Starring: Brian Downey, Michael McManus, Jeffrey Hirschfield, Xenia Seeberg

45 minutes. Originally aired March 15 , 2002

Rating (a 1 6 scale): 5.5

Chess players will love Lexx , “The Game” (4.18) . Only a very few feature-length movies have been made in which chess is the main subject. I know of only four. Three of these have as their central theme the idea that chess players become obsessed with the game and go insane. This is depressing, tiresome, and not exactly true due to the fact that the majority of chess players are already insane before they take up the game.

Lexx “The Game” (4.18), is an episode from a TV show, and with the commercials removed its only 45 minutes long, so whether or not it qualifies as a feature-length movie is debatable, but in any case it stands head and shoulders above the flicks whose directors are obsessed with proving that chess players are obsessed. Lexx (4.18) focuses on chess itself and succeeds in conveying many essential truths about the game.

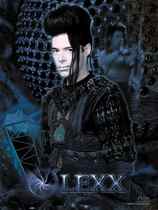

If Kai wins, Prince will free Kai from the ranks of the undead. Zombies are undead, and so are vampires, but Kai appears to belong in a third category. His spirit has been separated from his body. Only if the two parts of him are reunited will he be able to finish his life and find rest in death.

Kai and Prince play their high-stakes game in the middle of a bleak, lonely, windswept landscape in the Other Zone, which is defined by Kai (rather wittily, I think) as an “unstable partial universe. The Other Zone landscape (in reality an isolated location in Iceland) consists entirely of snow and rock a world of white and black with virtually no other colors, the perfect setting for a game of chess.

The chessboard and pieces deserve a careful description. Each of the boards sixty-four squares has a hole in the middle and is divided into two hinged halves that can be separated and closed again, similar to the two planks on a guillotine that clamp around a victim’s neck and hold his head in place so that it will stick out through a hole and be properly positioned under the blade. Various characters from the Lexx show wear distinctive hats to indicate which piece they represent (for example, Xev is the Black queen) while standing out of sight underneath the board with only their heads sticking up through the holes in the squares.

Goofy oversized keyboards protrude from two sides of the board. When one of the players is ready to make a move, he punches keys and turns cranks. The necessary squares open up, an unseen mechanism underneath the board slides the chosen piece to its new square (all we see is a head gliding across the surface of the board), and then the piece is clamped in place as the two halves of the new square close tightly around the neck of the head. Whenever a piece is captured, the square is cleared by an ax or mace that swings down and smashes the head of the captured piece like a ripe melon, splattering the faces of the other pieces with gorgeous gouts of fake blood and brains.

How, you ask, could such a lurid, garish depiction possibly reveal essential truths about chess? Let me count the ways.

First, Kai is unnaturally logical, rational, and imperturbable. He seems completely detached from other people. He cannot feel emotions and makes no attempt to feign them. He has no spirit. The look in his eyes is cold, empty, and profoundly inhuman. Prince, on the other hand, oozes all of the emotions that normal people find repulsive and loathsome. He gloats over the board, sneering at Kai with oily arrogance, his eyes glittering with sadistic glee. His theatrical gestures, his haughty tone of speech, his disdainful facial expressions, and his endless bragging make it clear that he considers himself superior to everyone else in the universe. Now, I ask you, isnt it true that these two personality types cover about 90% of all the tournament chess players youve ever met?

Second, the entire game is shown clearly from start to finish. Its a Bishops Opening melee featuring the complicated double-edged tactics that arise when one player castles kingside and the other castles queenside, with a race to see which player can checkmate the other first. Since Im a low Class A player myself, I couldnt be sure, but the quality of the play struck me as being quite high, so I guessed that the creators of the show were using the score of an actual game between two strong players. Later my guess was confirmed when Jeremy Silman told me that the game comes from the famous 1834 match between Labourdonnais and MacDonnell. I may have even seen the game before.

Fifty years ago, shortly after I discovered that I could use chess books to learn tricky openings that would allow me to crush my pals at Smiley Junior High School, I became infatuated with the swashbuckling but totally unsound MacDonnell Double Gambit and played through most of the games from the above-mentioned 1834 match. But I digress. The point I want to make is that the game shown in Lexx (4.18) is a good one, and after every move, Kai, Prince, and the talking-head pieces discuss the purpose of the move and debate its merits. This ongoing analysis is fairly simple and rudimentary but also accurate. As a result Lexx (4.18) can be used as an instructional DVD for beginners. By emphasizing the importance of relentless analysis, it reveals another essential truth about chess.

Third, when the talking-head pieces are arguing about tactics and strategy, they also bombard each other with a non-stop barrage of childish taunts, threats, insults, jeers, and sarcastic remarks. Whenever they think Kai has blundered, Princes pieces chant, “Resign! Resign! Resign! or “Bad move! Bad move! Bad move! After a capture, one piece ecstatically exclaims, “The violence! Oh, the violence! Reacting to what appears to be a blunder, another piece snickers and asks, “What are you, a retard? Finally, they are reduced to shouting “Nana nana na na! at each other like a roomful of sugar-crazed seven-year-old brats. In this way “The Game” reveals the most essential truth of all. It shows us the heart and soul of chess.